Uganda Chocolates

25 August 2010Introduction

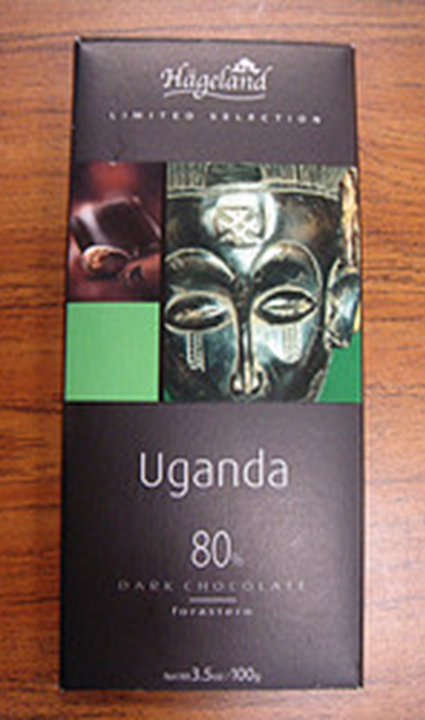

'Uganda Chocolates Sold in Canada' was the head-line of a news report published on 1 August 2010 in African media. Interestingly these chocolates are manufactured in Belgium using cocoa from Uganda that lends it a special taste so that the manufacturer thought it fit to promote it by the name 'Uganda' to represent a distinctiveness from other chocolates available in the market. How well and different it tastes can be judged from the following report of a blogger from where the picture of chocolate bar shown below is taken.

The blogger, a fan of dark chocolates who has not been getting darker than 70% easily describes his experience and joy of its taste as follows: ... "The chocolate had a very firm snap, and right away tasted a little bitter (but not unpleasantly so). It had a crumbly melt, and as it warmed, it tasted fruity and a little sour or lemony. The finish was earthy and clean (like a chocolate umami, perhaps), with no oiliness or weird aftertaste. The bar was thoroughly interesting, and actually, very good. I wouldn't want to eat it all the time, but I really enjoyed it"

The title of the above news-item in African media caught attention of a prominent think-tank of intellectuals wherein one member raised concern with the question - Any issues of intellectual property rights infringement, exploitation and value-addition opportunities here? What should Uganda do next? How can we, as experts on these matters, help her? In other words, the question was how can Ugandan farmers command a premium on their cocoa sold in international markets? This implies that Ugandan cocoa be protected as an intellectual property before such issues can be resolved. In fact, the 'intellectual property' on such matters has become quite central to international affairs and trade of commodities such as this in recent years. Products of this kind are now being increasingly protected as 'geographical indications (GI)' which is a form of 'intellectual property'. European producers of high premium products such as wines and spirits have been seen remarkably aggressive and successful in consolidating their position in international trade negotiations and are reaping handsome gains. However, many developing countries representing their 'traditional products' worthy of being granted GIs are lagging behind due to poor resource base and lack of appropriate legal framework and management and support structures.

The description by the blogger above suggests that products like Uganda chocolate will remain in demand in international markets due to its characteristic taste of cocoa grown and processed by the Ugandan farmers. In fact, the back cover of the wrapper of the chocolate brags, "Uganda is known for its generally tropical climate and fertile soils blessed by regular rainfall. Ugandan cocoa beans are highly sought after as consumers have discovered the exciting taste of Africa. Forastero beans in Uganda are renowned for their classic cocoa flavour and low acidity. The high cocoa content of this rich dark original chocolate provides a supreme cocoa taste with hints of earthiness, mushrooms and a subtle smoky flavour". Apparently, therefore, this looks to be a good case for consideration of the grant of GI that would entitle it to command a premium price on its sale in international market. In fact, GI has turned out to be more of a tool for international marketing than the 'intellectual property' alone.

What is 'Geographical Indication (GI)'?

'Geographical Indications of Goods' are defined as that aspect of industrial property which refer to the geographical indication referring to a country or to a place situated therein as being the country or place of origin of that product. Typically, such a name conveys an assurance of quality and distinctiveness which is essentially attributable to the fact of its origin in that defined geographical locality, region or country.

Although GI has been as part of the national law in different forms of some countries for more than hundred years now, yet its universal acceptance and the way we now know it as a specific form of 'intellectual property' is of recent origin when it was introduced in the TRIPS agreement of WTO which came into force since 1995. Many countries have since embraced the concept through passage of their own law on the subject. For example, the Indian Parliament passed 'The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act, 1999' in December, 1999.

India's Journey on GI Route

The first application received by the Indian GI Registry that was set up soon after the Act and the bill being passed was for Darjeeling tea in October 2003. It was filed by the Tea Board of India, an authority established by the government. Due to the special weather and soil conditions in the region, Darjeeling tea has a unique taste and is traded internationally. This was the first GI case in India granted on 29 October 2004. It is worth recalling that the quality, reputation and characteristics of the Darjeeling tea is essentially attributable to its geographical origin and cannot be replicated elsewhere resulting in Darjeeling tea being considered a GI. There are two main factors that contribute to its exceptional taste - the geographical location and the method of processing which is quite different from that adopted elsewhere.

This was followed by a spate of products from different regional stakeholders for registration of GI for their products e.g., Pochampalli ikat, a fabric (2004) and Chanderi sari, a wearable textile (2005). More than 100 GIs have since been granted in India and as many are still under consideration. It is reported that most of the products aspiring for GI status are in the category of 'handicrafts' followed by 'agriculture'.

Getting products on GI list is no mean task. One of the papers suggested for further reading at the end of this article outlines the treacherous journey of seeking GI status for such products which invariably involves a battle through the maze of opposition, vested interests of middle men, legal complexities etc. and the key to success being creating awareness among the stakeholders and provision of appropriate institutional framework. Getting products on the GI registry is only the first step towards realising their economic potential. Even this has been a major problem. Most of the people engaged in the production of such products are small households or small units, although in the same area. Convincing them to organise into associations to move the application for registration was a Herculean task in many instances. This Indian experience of getting GI status for a large number of goods that come from small stakeholders from artisanal or farmer classes but having unique qualities to merit such protection should be a valuable lesson for many African countries.

Cocoa Cultivation in Uganda

Cocoa was introduced in Uganda by British in 1903, but has become important for domestic or export markets in only last few decades. The government wants to see a rapid rise in the quality and quantity of production due to a huge market demand - it has plans to plant 35 million improved cocoa seedlings over the next seven years. It is estimated that currently some 15,000 metric tonnes of cocoa valued at US$30m is exported. In fact, Uganda is not the only country producing cocoa in Africa; Cameroon, Ghana, Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa are other countries very much into it and almost half the national economy of some of these is based on cocoa production alone. Much of the cocoa production in Africa is in the hands of small farmers having plots of less than 3 acres and is characterized by employment of children which is a point of controversy in the western world. There also is considerable smuggling of cocoa in many parts though Cocoa Marketing Boards are also in operation and sell the product on fixed prices. Ugandan President was reported to comment once that he would like Chocolates to be produced within the country instead of exporting cocoa out of the country.

Bundibugyo, a district in Uganda that produces much of the country's cocoa has got a bumper crop this year while there was little last year due to drought like situation. People are raking in money this time around and getting busy with constructing new houses and buying cloths for the family as well as putting children in school. This sudden prosperity is stated to be a cause for worry also since people are planting more cocoa trees instead of food crops with the result that there is considerable shortage of food and malnutrition among children is increasing. More money in hand is also turning men into polygamy with a tendency to have more number of wives. The government is addressing these problems by creating awareness for maintaining balance at home and at the farm. What we are concerned here, however, is a sustainable development of the region based on a quality production of a product for which there is a perenial global demand and ensured income.

Cocoa is a major earner of foreign exchange in Uganda. To get the best price, quality is essential and for this the cocoa must be dried until its water content is about seven per cent of its weight. Too much moisture affects the cocoa's scent and flavour and can encourage the growth of mould. Cocoa beans with fungi cannot be used to produce chocolate. For this, new drying technology transferred from Italy is being tried harnessing the solar power that uses 200 mm thick polyethylene sheets that retains the heat underneath. This technology helps the growers comply with regulations of the EU good agricultural practices.

In international market, cocoa is graded in two categories; conventional (where chemical fertilizers and pesticides are used) and organic (where farm yard manure is used to improve the fertility of the soil and also boost yields). Organic cocoa fetches a one and half times more price than the wet conventional one.

GI Laws in Sub-Saharan Africa

Justin Hughes' report (Please see reference below) produced for the International Intellectual Property Institute, Washington, though still at the draft stage reviews the current status of GIs and concurrent laws on coffee and chocolate products with a view to examine how developing country farmers can be helped through GI regime. It states that just as GI laws and broad GI-based marketing are relatively new in most developed countries, such laws and explicit marketing are rare in the developing countries that produce coffee and cocoa. The report provides interesting insight into Jamaica's struggle for the GI of its 'Blue Mountain Coffee'.

Examining through the impact of GI-based marketing and the need for public enforcement of GIs both in the producing developing countries and elsewhere in developed world, it has been suggested that cocoa-producing states can market both GI-based cocoa and GI-based chocolate. For example, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela each have at least one premium quality chocolate producer with meaningful exports to developed countries; in 2007-2008, 20% of Côte d'Ivoire cocoa production was processed locally into cocoa butter, cocoa powder, and chocolate.

Millions of people in the developing world have stake in GI-based production and marketing. There are approximately 6.5 million cocoa growers - mainly farmers and their families working small plots, about 70% of these people are in sub-Saharan Africa. It has been concluded by the author that while domestic laws complying with TRIPS Article 22's standard for the protection of geographical indications unquestionably provide the needed environment for successful

GI-based marketing, but very few developing countries have such laws.

The first real challenge is building up the reputation of possible coffee or cocoa GI candidates. This is stated to be achievable though as Colombian coffee demonstrates. It was observed that

most investment in coffee and cocoa GI reputations is now being made by coffee roasters and chocolate makers from rich economies - and developing countries should welcome this instead of trying to stop them. The stark reality, however, is that many coffee and cocoa producing countries do not have the government resources, public institutions, and transparency to make any meaningful progress on this front.

Catherine Grant (Please see reference) while discussing GI implications for Africa argues that that the greater protection of GIs would benefit farmers and craftsmen in Africa by assisting to market their products. To achieve this, however, African countries need to stand together in international discussions instead of dividing themselves into groups. They also need to identify key GIs that are worth protecting.

Status of IP / GI Laws in Uganda

Having begun our story with Uganda, it is prudent to conclude with a quick review of the status of IP and GI laws in that country. The country has several IP laws presently existing but they are yet to be TRIPS complaint which it is under obligation to do by 2013. The country's IP administration and enforcement is extremely poor at present despite the fact that it received cooperation and funding to upgrade the system from various quarters. The bill for the GI law is stated to have been passed very recently but lot more needs to be done.

Let us hope there would be positive developments in future that would ensure supply of quality chocolates from Uganda and bring the desired prosperity for Ugandan peasants. We may ask - when 'Swiss Chocolate' is already a GI, why can not 'Uganda Chocolate' be so? But the answer to this question has to come from within Uganda.

Note - The pictures in this article have been taken from the references given below for further reading!

- Raustiala, Kal and Munzer, Stephen; Global Struggle over Geographical Indications; Research Paper 06-32, UCLA School of Law.

- James, TC; Protection of Geographical Indications: The Indian Experience ; ICTSD, Vol 13, No. 3, September, 2009

- Hughes, Justin; Coffee and Chocolate - Can we Help Developing Country Farmers through Geographical Indications?; - A Report Prepared for the International Intellectual Property Institute, Washington, D.C., 2009 (DRAFT)

- Grant, Catherine; Geographical Indications: Implications for Africa; A Report Prepared for Trade Law Centre of Southern Africa.

- Technical Assistance to the Uganda Ministry of Tourism, Trade and. Industry in the Area of Intellectual Property Rights. Project Reference: 9.ACP.RPR.007; Prepared by the International Institute for the Advanced Study of Cultures, Institutions and Economic Enterprise (IIAS), Ghana, 2009

- Wamboga-Mugirya, Peter; Hot chocolate: Uganda's Solar-Powered Cocoa Industry